Project: Azure Sphere and Microsoft Teams (with Microsoft Flow)

Azure Sphere is a Microsoft-created solution for IoT devices. It’s a combination of certified hardware, an OS and a cloud service. It’s designed to be secure with multiple layers of security but also provide features such as Over the Air updates of code and automatic updates.

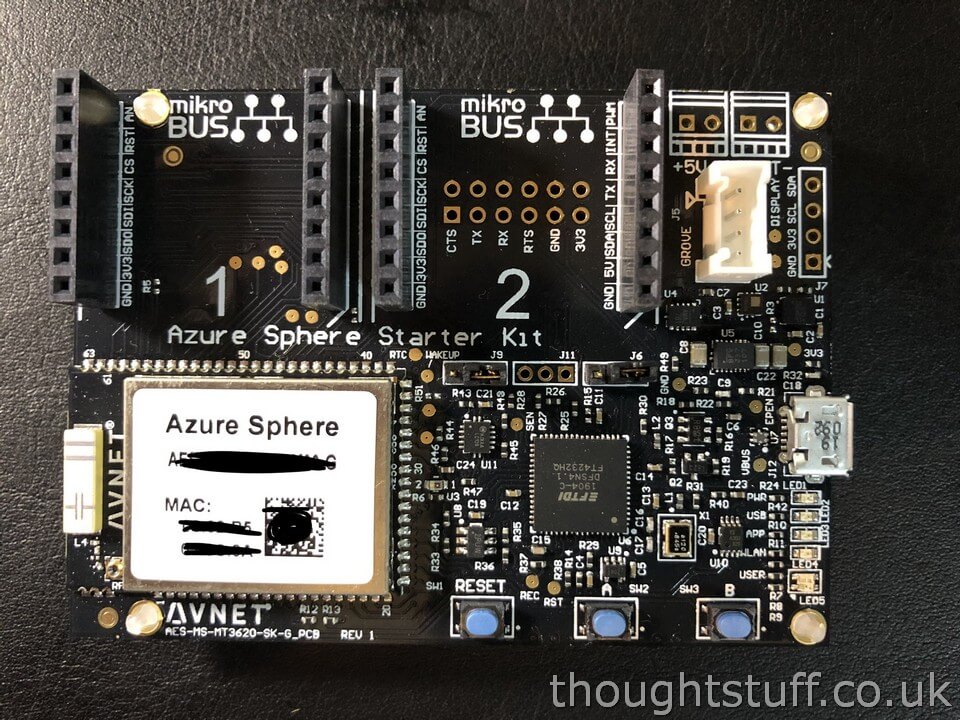

Due to one of the strange stock inventory realignment events that sometimes happens with electrical warehouses, I managed to get one of these devices for basically no money. I got the Avnet MT360 (shown above). It came with a USB cable and no instructions. I am NOT a very good low-level programmer by any means, but I had this device now, so I wondered what I could do with it.

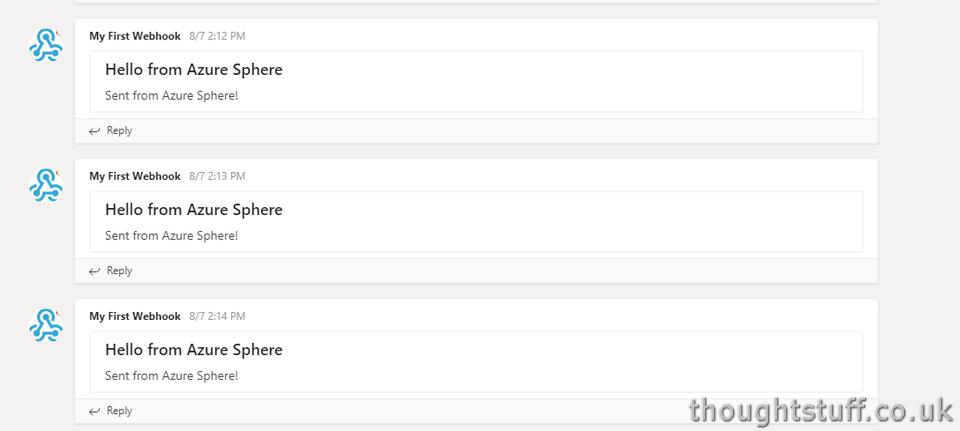

There is WiFi on board (5G!) so I thought it would be fun to see if I could get it to post something to Microsoft Teams. I’ve posted previously about a really simple way to send messages to a Teams channel using a Connector and PowerShell (here’s the Gist to do that) and I thought that it should be possible to do something similar from Azure Sphere – it’s just a POST request after all.

Happily there are some good samples for Azure Sphere, including this one that downloads a webpage over HTTPS using cURL. I’m no C programmer, but even I was able to take this sample and re-work the GET request to be a POST request, add a Content-Type and body, and get it posting to a Microsoft Teams channel:

Here’s my GitHub project for this – periodically posting to a Microsoft Teams connector using Azure Sphere.

Use Case – Temperature Monitoring & Alerting

I still didn’t have a real-world example, but I wanted to try something more advanced. The board has a temperature sensor on board (also pressure and accelerator), which formed the basis of my example use case.

Let’s say I want to monitor the temperature of a critical piece of infrastructure. If the temperature goes over a certain threshold I want to post a message in Teams, in a specific channel.

Let’s set up the example:

This is the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant team. Within it are channels for various parts of the facility. We’re interested in Sector 7-G. If the temperature of the core goes above a certain level then we want to add a message here, to help out the safety inspector. Bonus points for also alerting people in some visible way. Once the temperature falls, post another message and remove the alert.

Disclaimer: if you wanted to do monitoring of temperature over a long period of time and analyse the data etc, there are probably better ways of doing this, such as sending the data to Azure IoT Hub first. This is just an example.

Avnet have a reference project showing how to get and log temperature, pressure and accelerator activity and send it to IoT Hub. My plan was to take this sample, extract just the temperature measuring part, and then smash it together with my Hello World POST example.

It was a bit of a painful process for me – a high-level, sometimes still codes C#, okay-ish developer. There’s a surprising amount of abstraction between C and C# which I’d forgotten about, but which I was gently (and not so gently) reminded of. However, by changing things slowly and trying out different approaches, without needing to go and study in detail how temperature was obtained, I was able to extract that part from the reference project and merge it with the HTTP POST project.

Fairly early on, I decided that it would be a Good Idea to do as little work as possible on the board, and as much as possible elsewhere. The ‘business logic’ of this example, such as working out if the temperature was above or below a threshold and doing something in response, should be done somewhere else. I settled on Microsoft Flow as a good no-code solution to this problem.

It’s possible to make a Flow that is triggered by a POST request to a unique URL. By POSTing to this URL from my Azure Sphere code and including the temperature in the request body I could have Flow make all the decisions and take all the actions. That meant less time in C and more time happy. 🙂

The Sphere code for this example project is here. It works on a 60 second timer, posting to a Flow endpoint URL with the current temperature in the request body as JSON.

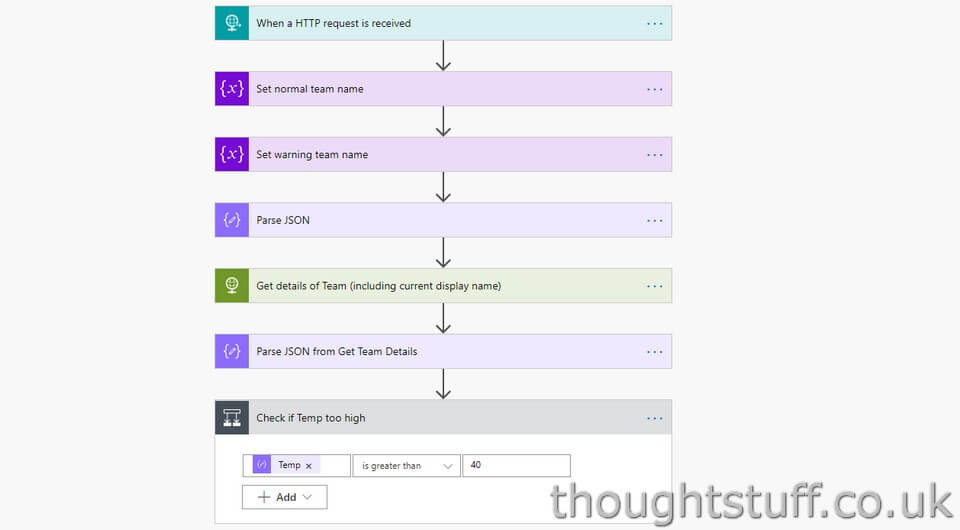

Here’s what the Flow looks like as it starts out:

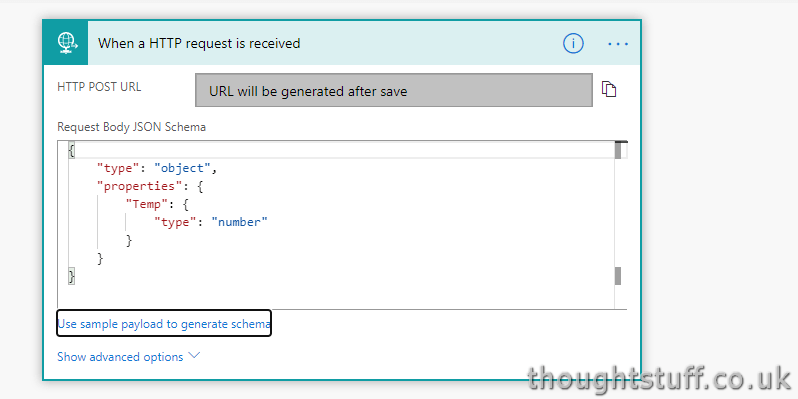

What’s going on here? Well, the first box is the HTTP request. I had to tell Flow what the request body schema was. I used a sample payload to generate the schema because I’m lazy and it’s better than I am at doing it:

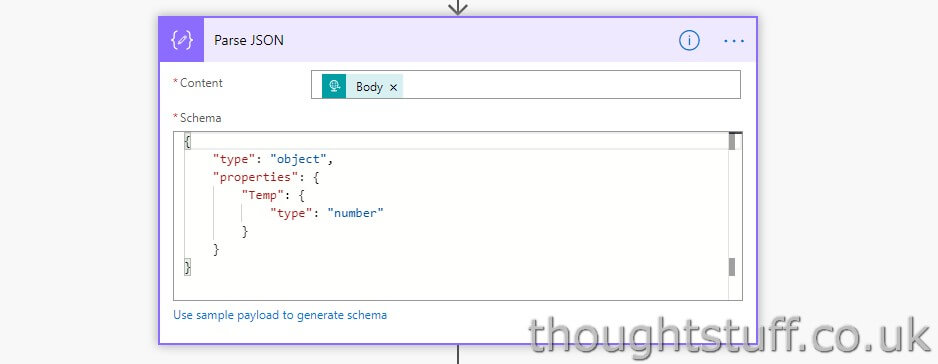

The two variables are for later, so can be ignored for now. The Parse JSON box is taking the body from the request and parsing it to pull out just the temperature (using the same schema as before):

Ignoring the next two boxes, the last box is a check of the temperature against the threshold. This then gives me two different paths to go down, depending on whether it’s too hot or not:

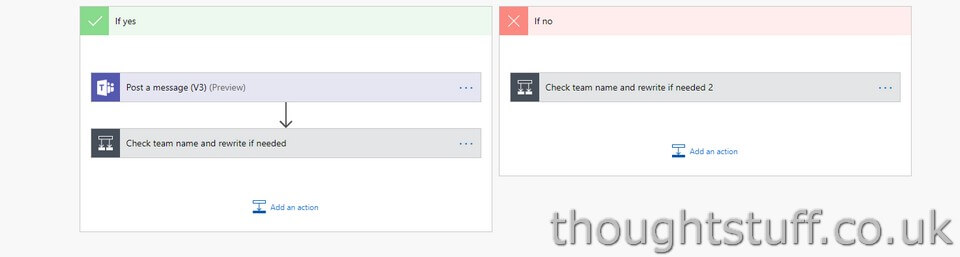

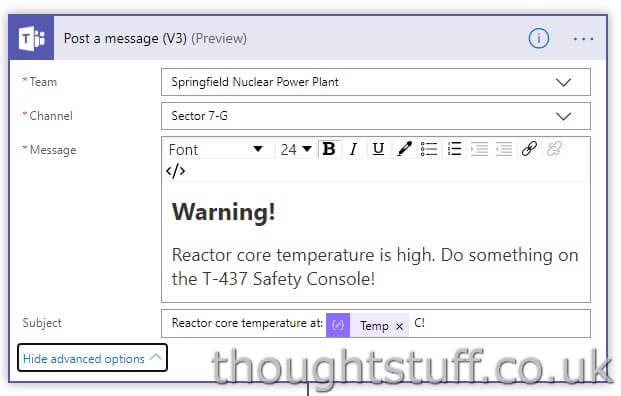

In my first iteration I just posted to Teams using the built-in “Post a message” action:

However, I wanted to do something a bit more clever than just post a message. Just because it’s not a built-in Flow Action, doesn’t mean you can’t do it. One of the API calls in Graph enables a PATCH request to update a team or a channel. This allows you to change a team setting, or channel name etc. I wanted to use this to change the name of the channel to make it more obvious (to a distracted Homer operator) that there was a problem. (this is probably a blog post in itself but rough details below)

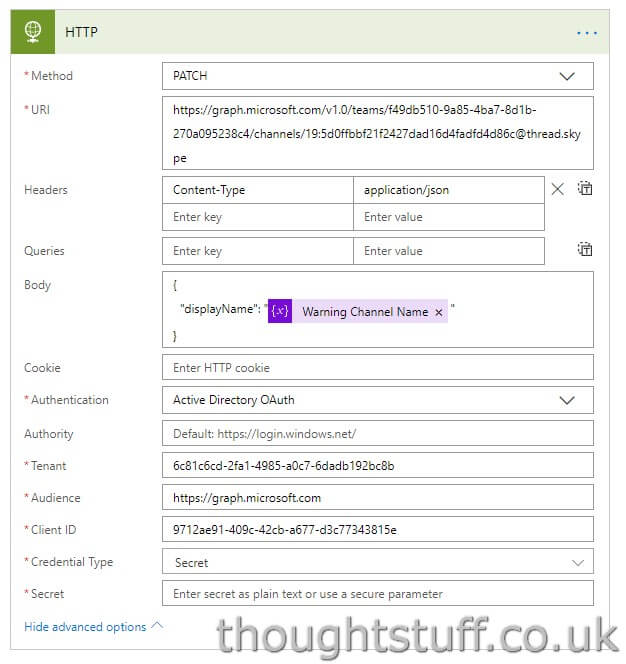

To do this I set up a new Azure AD Application with the right Application permissions to update (Group.ReadWrite.All) and then issued a PATCH request using the HTTP action:

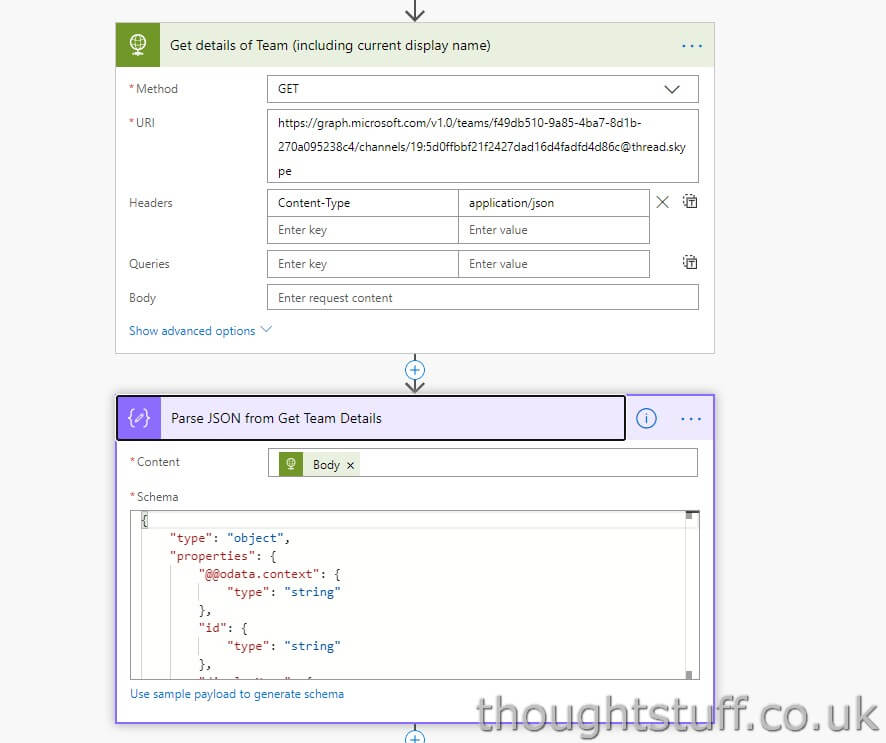

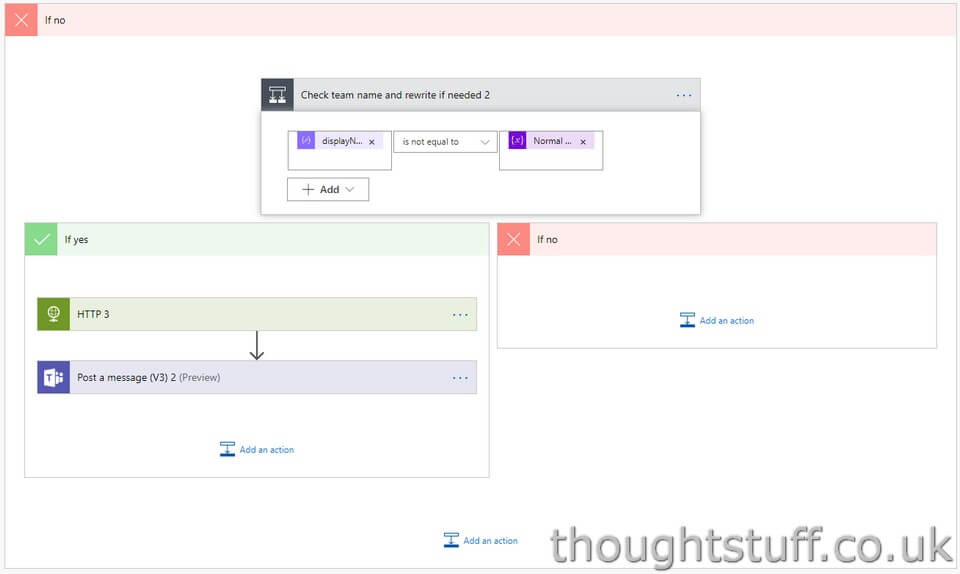

However, this gave me a problem because Graph will throw an error if I try and update the channel name to be the same as itself. So… I use another HTTP request to first get the current name of the channel, and then use that to determine whether or not to issue the update PATCH request. This is the reason for the boxes I glossed over before:

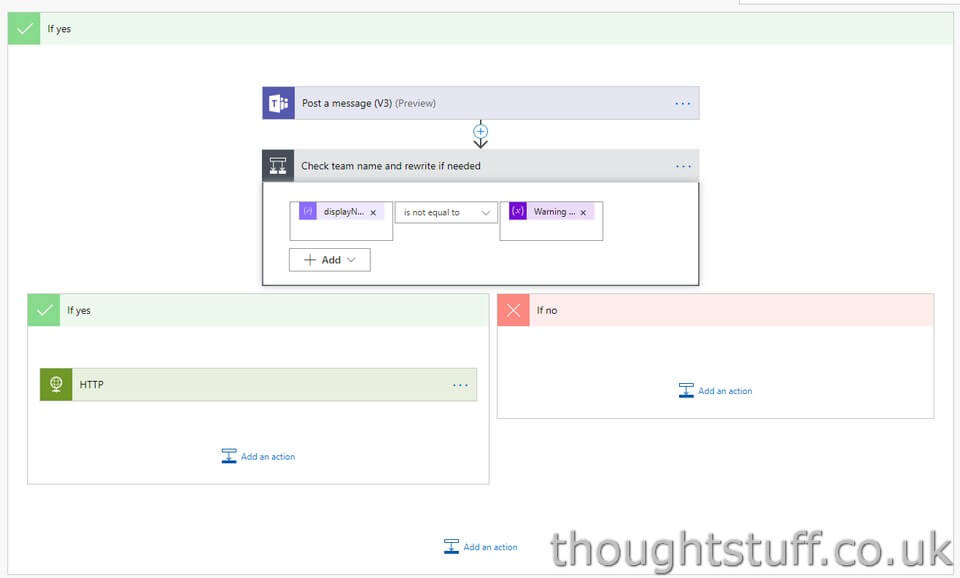

I’m also using information about the channel name with slight differences on each side to make sure that the warning message is sent every 60 seconds, but if the temperature is below threshold, only send that message the first time, not every time. This is all easy to do in Flow but would have been really hard to do on the Sphere (not impossible at all, just harder). This is the “above threshold” flow:

and this is the “below threshold” flow (notice the different placement of the ‘Post a message’ action here):

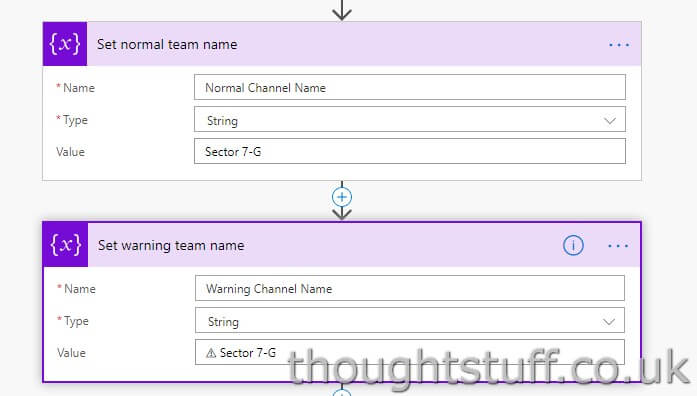

Because I use them in several places, I made two variables to store the ‘normal’ and ‘warning’ channel names to use. I’m adding a warning triangle emoji for the warning one:

The Big Demo

Once an Azure Sphere app is written you can deploy to the Azure Sphere Service and associate it to any number of devices you own or are in control of. That way, when the devices power up they check in with the service and download the latest version over the air. It’s a really nice deployment model, especially at scale. It meant that once I’d written my program I could remove the Azure Sphere from my computer (where you can plug in it for debugging in Visual Studio), and use a battery pack to run it anywhere!

(Un)fortunately, I didn’t have a nuclear reactor core to try this out on, but I did have a hair dryer:

Get all the code

I’ve linked to parts of the project through this write-up but if you’re looking to just download something and play, here you are:

https://github.com/tomorgan/AzureSphereMicrosoftTeamsSamples

Conclusion & Futures

I’m pretty pleased with how it all turned out. It was actually easier than I thought it would be to get something to sample the temperature and get it into Microsoft Teams.

Based on the success of this project, I’m now looking at external temperature probes for another project to monitor soil temperatures. Maybe if I can get that to work I’ll do a follow up post. If anyone is doing anything similar with Azure Sphere and wants to give me some pointers, always happy to learn! 🙂